“Long winter for Old Masters” headlined the Financial Times’ Collecting section this past weekend, referring to the bad performances of London Old Master auctions the previous week. Although Georgina Adam is right in making this statement, what isn’t mentioned is the serious lack of good quality paintings on offer, the ridiculously high estimates given by auction house experts, and a headline lot failing to sell because of authenticity concerns. The Christie’s cover lot Hans Hoffmann’s watercolor on vellum “A hare among plants” (1582), was estimated at an optimistic £4-6million and failed to attract a single bid! No surprise to some who were questioning its authenticity, believing this to be a later copy whose provenance got mixed up sometime in its history.

Yes the Old Master market is struggling but there is still strong demand for internationally collected artists. What is troubling is that it has become harder to find good quality paintings and the collector base is quickly diminishing. The Old Master dealers cannot keep on running their galleries like they are used to and even the great, dealer-run TEFAF in Maastricht (since the 80s) needs a serious change over to re-excite the old time goers and attract new audience. They need to change and adapt to the current art market, which is completely dominated by contemporary art. Since Old Masters cannot compete with the parties and dinners given in honor of artists, it has to patiently try to engage with a new audience and get them excited about buying and living with Old Master paintings and drawings. For a new collector, I would highly recommend to start looking at drawings. Both from a price point of view and aesthetically they are easier to fit with a contemporary and modern collection.

Here are 7 useful tips on collecting Old Master drawings from Christie’s specialist Benjamin Peronnet:

- Delve into history

Old Master Drawings are often intricately linked with the history of the country in which they were produced: 17th century Holland, for example, was an iconoclast Protestant country, so there were almost no commissions for religious paintings — and, with no real aristocracy, King or court, most art was bought privately. Drawings of landscapes or genre scenes were often viewed not as sketches but as highly finished works of art. These drawn works tended to feature the artist’s signature, and mirrored Dutch paintings.

Italian drawings, however, show the influence of the Church, which played a huge role in artistic patronage. The important commissions the Church gave required extensive preparation, and a significant number of Old Master drawings from that country are in fact studies of figures and compositional sketches for larger works. The same is often true of French drawing, though in the 17th century the disciplines of French Classicism meant drawings in that tradition were less Baroque than their freer Italian counterparts, which conveyed a greater sense of movement.

- Familiarize yourself with artists’ preferred techniques

Often, 16th and 17th century artists would begin a larger work by quickly sketching their intended composition in pen and ink, often over unobtrusive indications in black chalk. Drawings made with a rapidly wielded pen were ideal for exploring an initial idea.

For greater precision, artists used chalk to more carefully depict individual figures, and to study the fall of light and shadow. Blue paper worked well with chalk — with artists often choosing two shades from black, white or red, and sometimes all three.

Once these initial sketches had been made, an artist would move on to the modello, a finished study close to the final composition, and this would often be submitted to the patron for approval. These might even have to be squared, to allow the artist the more easily to transfer a composition from paper to canvas — or, in the case of a fresco, to the wall.

- The whole is greater than the sum of its parts

In the field of Italian drawing, most collectors look for depictions of the figure, while, for Dutch drawings, landscapes tend to be most popular. But there always are multiple exceptions, such as Rembrandt’s wonderful figure drawings, which are very much sought after. When looking at a drawing, I would consider its quality, not its adherence to a particular theme. The object itself is important, sometimes even more so than the artist.

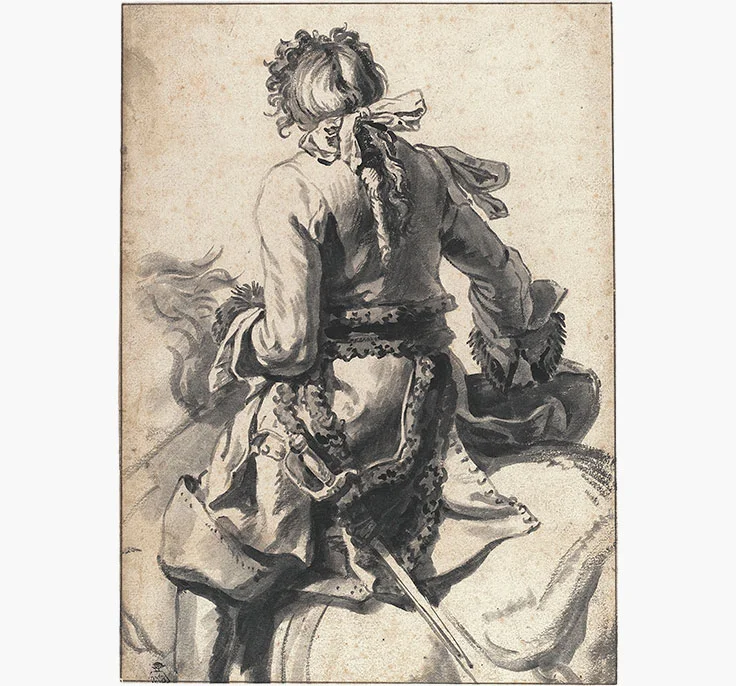

For example, Christie’s recently sold a drawing of a cavalier by Pieter van Bloemen, a rather minor Dutch artist of the 17th century. Everyone who saw it loved it — everything was perfect in condition and composition; it had a special kind of charm. It sold for £253,250, well above its estimate of £3,000 to 5,000. The record price for a van Bloemen before then was around £4,000 and similar drawings have since sold for less than £10,000, but this drawing was special.

- Old Masters can be affordable

Works we have sold range in price from £700 to £26,000,000. Yet over 90 per cent of drawings have a market value of less than £10,000 — only a very small proportion are worth a fortune. It is absolutely possible to find very good drawings from good, well-known artists for £4,000–5,000.

You can find a perfectly nice little drawing executed by Fragonard during his early days in Italy when he was copying the Old Masters for £4,000 to £6,000 (see above), or even a little Jean-Louis-André-Théodore Géricault. The students and followers of Ingres working in the 19th century such as Alexandre-Jean-Baptiste Hesse, Savinien Petit and Félix-Joseph Barrias were gifted technicians whose beautiful drawings sell for around £1,000 to 1,500, sometimes less.

- Look out for suspicious signatures

The signatures you see on drawings can often be inauthentic, or misleading, later additions to the works. The number of drawings attributed to Raphael or Michelangelo is enormous. That is where a connection to a finished painting is important, and you should be ready to pay a bit of a premium where the attribution is beyond doubt. The experts use their eyes, consult literature and ask the opinion of external scholars.

- Store drawings with care

The value of a drawing can be slashed 10 times if its condition is poor. Exposure to sunlight leads to fading and discoloration of the paper and the ink tends to sink in to the paper and damage it. This used to mean a collector could not always enjoy a collection on his walls. But today there are ways to avoid damage from the light such as the use of UV-resistant glass, even though one must always treat them with care.

Drawings can also suffer from insects like silverfish that eat the paper. Depending on the medium, humidity can also be a problem. For others, it is storage that has been an issue: drawings can be found folded, or with smudged portions, having been left unframed and unprotected.

But we should not paint too gloomy a picture; most drawings have survived the test of time surprisingly well.

- Hold it in your hands

People are afraid of entering drawings departments in museums because they feel they are reserved for scholars. This is not true — most of them are open to the public. Visiting museum collections gives you the opportunity to see drawings unframed, just mounted: that is the best way to approach them. You used to be able to go to the British Museum unannounced and see whatever you wanted. The rules have changed since but you can still explore the far reaches of the collection if you write to them two weeks in advance. The same applies to many of European and American collections.

England has incredible drawing collections at the British Museum, Oxford’s Ashmolean Museum and Cambridge’s Fitzwilliam Museum, and Scotland has treasures too. In Europe, visit the Louvre in Paris, Florence’s Uffizi, and Holland’s Rijksmuseum, which has an especially beautiful collection of Dutch drawings. The United States has New York’s Metropolitan Museum, the Getty Museum, the National Gallery of Washington, and the Art Institute of Chicago, among others.

There is something very immediate about a drawing, and you only get a sense of its physicality when you have it in your hands.